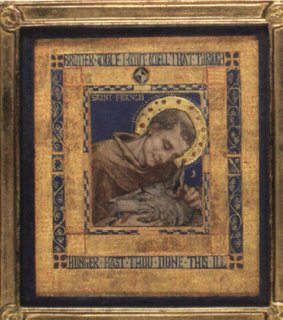

"Oh, St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio- what a cute story. The wolf who eats people and then becomes nice because St. Francis spoke to him. That's neat."

Wait a minute.

A people-eating wolf who becomes their pet because of a saint? That isn't a cute story. Either that is total fiction, or it needs some thought. Legends about saints, especially those who drew out their lives- like pure water from the well of God- hundreds of years ago, are rife. How do we sift through that which is pure fiction from those stories which hold truth?

Legend, especially in the area of hagiography, is a more complex area of study, because there is usually some grain of truth, some part of the saint's spirituality which so struck those around him or her, making stories grow and spread over miles and generations. The importance of the legend, it seems to me, is not the details which vary just about every time you hear it, but rather the truths about the God-infused person who is the center of the legend.

Here is the story of the Wolf of Gubbio, in short: St. Francis, after he had been espoused to Lady Poverty for some time, heard about a town called Gubbio, whose inhabitants were menaced by a ferocious, giant wolf. The wolf had figured out that Gubbio was a place where there was an endless supply of food- unfortunately, he had taken a taste for people. So frightened that they would not come out of their houses, the people now survived in a state of near anarchy.

St. Francis, hearing of their situation, traveled to Gubbio and learned the whereabouts of the wolf's lair. He walked right up to the entrance, and the wolf rushed out with teeth bared, ready to feast on St. Francis then and there. The saint held up his hand and ordered the wolf to lay down. He then spoke to the wolf and rebuked it, ultimately making a bargain with the wolf: if the townspeople agreed to feed the wolf, the wolf would leave the townsfolk in peace. The animal agreed, nodding its great, shaggy head, and placing its huge paw in the hand of St. Francis. For two years, the people fed the wolf, and when it died, the people mourned it.

The image that draws me into this legend is that of St. Francis traveling towards the entrance to the wolf's lair. What would he have been thinking, or praying? Would he have been sure that God would exercise His power to tame the wolf? Was he placing his own life in the hands of Our Lord, caring not whether he lived or died, in hopes that the suffering people of Gubbio would find relief? Was he thinking of the parents who had lost children in those evil times, and hoping that with the change of the wolf, the parents would find hope in the power of God to heal suffering? What kind of man would face a wild animal without weapons?

There are some clues in the rest of the life of St. Francis which can help us flesh out this part of his character- and spirituality. There is something almost wanton, but a wantoness with a sure love and deep passion for God, in the well-documented instance of St. Francis coming out from behind the Bishop's tapestry with nothing on, in order to give everything back to his earthly father. It is a courage beyond earthly prudence, but not beyond supernatural prudence. Francis understood worldly prudence: he had lived it, and lived with an incarnation of it in the person of his successful merchant-father. However, he eschewed this prudence for the supernatural, like the merchant who finds the pearl of great price. Francis knew that the price of this Pearl is the espousal of Lady Poverty.

Another instance is the rule which St. Francis wrote for his new order, radically stark- and pure Gospel. In his reply to Pope Innocent III's concern for the 'impossibility of following such a rule', St. Francis' reply elucidates the man who could face a wolf with supernatural prudence: "Holy Father, these are the words of the Gospel. Our Lord lived them: who are we to water them down?" (paraphrased).

It was this courage based in absolute love of God that drew followers to St. Francis like bees to honey. It was that this man became so thin, thin of bodily frame as to have light shine through him, the light of the ineffable love of Christ, that made him a torch by which the love-starved thirteenth century man could find real love.

Inspired by God, the saint stripped himself of every comfort, of every modicum of status and power, all that was easily in his grasp based upon his family background. This sounds so familiar to us now, that the radicality of it is largely lost on us, so that we reduce it in our lives to a 'willingness to be detached' but no actual action; when in its reality, St. Francis' actions were and are unthinkable to us in our natural state. To leave all normal society and follow in the invisible footsteps of Christ, to become a second Christ on His cross of ignomy and absolute poverty is not something we can even think about doing on our own.

St. Francis jumped into the call of the Gospel with all that he had, and reaped from his great loss of worldly comfort an amazing harvest of courage, love and joy. It was with this absolute-ness that he tamed the wolf. God was so present with him that the wolf responded to St. Francis as a creature to Adam before the Fall. It is the incredible dignity to which God calls us all: but the road is through poverty for the sake of God. This means something different in every life; we only have to understand the myriad of ways the saints traveled this road of absolute surrender: but the call to radicality is the same, for real love is radical.

It is not easy, I think, to be in radical love with God- but I think it is a beauty beyond compare, making the things of this world fade. The paradoxical mystery is that as we are impoverished in the terms of the world, the more we are enriched in God. We begin to live on another plane, and this carries with it what John Paul II called original solitude: the sense which a'dam had of his own body and the difference that the image of God placed upon him meant in relation to the world of all other creatures. Adam sensed a solitude: but it is through this solitude that we understand the need to search for and the meaning of communion- with God and with our neighbor.

The sense of solitude and emptiness of chosen poverty works, I think, in the same way as the solitude of Adam in creation (before Eve)- in that the awareness of oneself as completely naked(like Adam before the Fall, in acceptance of poverty, unashamed) and dependent on God enlightens us as to our absolute need of Him: thus are we truly prepared for His loving reply, I am always with you. Poverty, Lady Poverty as St. Francis so called her, on the levels of the body and the soul becomes the necessary incarnation for us of our absolute dependence on God ( a reality that comfort simply hides but does not eradicate). The dependence on God is the condition for our loving Him and Him loving us in truth: for without Him we are indeed impoverished. He cannot bring us to the true heights of love until we understand our real position; our real depth of poverty when we depend upon ourselves or creation for love instead of Him Who is True Love. Poverty, like the Cross, is a sign of contradiction to the world, but a sign of grace and love for those who seek Christ.

The wolf is tamed by a spirit steeped in the heights of love. St. Francis knew that if you try to steep a tea bag in more than one pot, the tea is weakened in its power and becomes insipid. Thus, he impoverished himself from the tea pot of the world in order to be totally God's, and he was made strong with the strength of Christ.