In the 2004 film production of Thornton Wilder's Bridge of San Luis Rey, there is a moment that stands alone in beauty and depth: the words, the scene, the faces of the actors, the looks captured; to me, this moment is the true flowering of the story.

The original book, to which this production is said to be 'slavishly' correct, is a story about a priest in eighteenth-century Peru who witnesses the sudden fall of an ancient foot-bridge, path to a popular place of pilgrimage. Five people perish suddenly; and it so affects this priest, who has begun to fall into the doubting of those who wish to understand before they will believe, that he makes it a work of six years to find out either God's providential designs for these five, or whether this was random. The conclusion would be final: either God exists or the whole universe is meaningless, and with a definite foundation of tragedy and sadness. However, the very question was the unbelief; for those who will not see (seeing is an act of faith in the spiritual) are already blind.

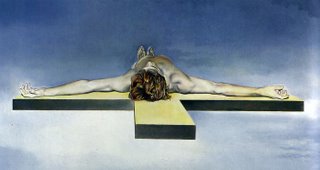

The priest traces carefully the lives of each person who fell to their deaths that day in the heat of Peru, and he remains inconclusive. It is the author, Wilder, who tells the real story, the story that the priest could not get to in his digging. We begin to see that each of the five people who died had suffered for love, they were, in a sense, the penitents, the ones who had finally learned what love really was: not selfish desire, addiction, lust, not a life in a peaceful garden, not even the ties of blood. They finally understood that love was to let go of all these, to look out of oneself to the ones God has put in one's life, and to learn to love as Christ loved: from the pilgrimage of the road, teaching and healing; from the synagogue, fighting hypocrisy;from their homes, helping the widow and the orphan; from the Cross, killing sin and death. To love is to lose one's life for the sake of Love, watering the vineyard of the Lord with one's own blood. To love is to love Love Himself above all.

This understanding the five came to, and as a direct result of their loving this way, they literally lost their lives: but what, again, is the end of that verse: "If you seek to save your life you will lose it, but if you lose your life, you will gain it". The five lost their physical lives but gained something more: it is apparent from the threads of the story that the omniscient narrator tells, they had gained love; and their blood watered the lives of those they left behind.

The most important of those whose life was radically changed by the death of those on the bridge was La Perichole. In the years before the accident, she was a talented and vain actress who had caught the eye of the Spanish Viceroy of Peru. She bore him a child out of wedlock, and was certainly on her way to perdition. But, in His mysterious way, the Lord had designs to save her, and the first deep knell heralding this redemption was her falling ill of smallpox. It destroyed her beauty and the surface sin of vanity began to be eradictated from her soul. The man who truly loved her, albeit imperfectly, came again and again to see her in her recluded state. She finally allowed him to take her son to Lima so that he could be educated. On his way, her friend and her son were two of those who died on the bridge.

La Perichole finally appeared at the convent in Lima, a broken and contrite woman, a woman ready to recieve Christ into her life. In the years that the priest was searching out God's providence in the fall of the bridge, La Perichole was living it. Living God's providence, finally understanding love, she was now "Sister Camilla".

The moment of beauty in the film comes when Sister Camilla appears at the court arranged by the Bishop of Lima and presided over by the very Viceroy with whom she had sinned. She comes into the court to give evidence in this trial of the priest, who is charged with heresy for trying to systematize and prove God's providential design (ignorantly trying to destroy a need for faith and make heaven on earth).

Sister Camilla flows into the court, her whole body and head veiled in a white-cloud habit, and stands easily and gracefully on the witness platform. The bishop asks the Mother Superior accompanying her, "Is this the woman who used to go by the name of La Perichole?"She answers in the affirmative and when Sister Camilla is asked to remove her veil to make sure, the Mother tries to vouch for her identity. The Bishop makes disparaging remarks about the honesty of a former actress, and without self-defense or reply, Sister Camilla removes her veil, revealing a horribly scarred face. The Viceroy winces, and the Bishop bids her step forward, asking the Viceroy pointedly if he recognizes her: after all, he knew her the best.

Sister Camilla steps forward, and looks up at her former lover, the Viceroy. To the shock of the court, he says after studying her face, "No. No. I do not recognize this woman. For all her passion, La Perichole had no love in her eyes."

Sister Camilla looks at her former lover for a moment, her eyes full of peace: and love: and forgiveness, for as some saint said, "Where there is true love, forgiveness is already there." She replaces her veil over her face, which despite all its scarring, has grown truly beautiful: beauty where before was only sparkling, hard charm.

Is this not the moment of God's providence? Are not those of us with scarring able to look yet beautiful, an eternal beauty, a spiritual beauty, a piece of heaven shining through the charred remains of our sin?

As the Sister leaves the courtroom in silence, the Mother Superior stops and says, "Those who will not see are truly blind."

See, oh see, the greatness of the Lord, see Him in all things, great or small: see Him in the sadnesses and storms, see Him in the calm and joy: for He is Lord of them all. May His face, a face scarred, a face of beauty in love, be our face; may His open side be the door by which we all enter His Kingdom.