A thirty-something mom who likes classical and Gregorian is an unlikely candidate to connect with a Tool song: but I did. The song is 10,000 Days (Wings Part 2), and it seems to capture, at the root, the feeling one has when understanding finally something of the cost of martyrdom. The creative man behind this song is the son of a Christian mother who was afflicted with a stroke and spent the last 10,000 days of her life paralyzed. Her son, a rock star, with some pretty dark and disturbing songs under his belt, seems to come up for air because of her death. I don’t have a judgment as to his personal faith or not, but to me he captured something profound in this particular song. He seems to be shocked into realizing that she is now facing her eternity, and he cries to God in this song for her salvation: he rages, how can she, who loved and suffered, deserve anything less than the greatest welcome from God? How can He not give her soul wings?

10,000 Days starts out in a harmonic minor, and by bridges, slowly layers on other harmonies and finally a clamored melody (like a journey upward). Using the minor key (think of Jewish music from the captivities), but starting out with the sinews underneath, bare and vulnerable, seems to me to be less purely sentimental than akin to the deep suffering that undergirds life in the world; and accepting this as the providential disjunct between this life and the next is a fundamental part of martyrdom for the lover of Christ. Back to the song: Waiting for the melody, the following is sung quietly, bemoaning the fact that many of our churches are filled with those (-is it I, Lord?) who consider themselves saints and martyrs for Christ, but who are actually hypocrites of the worst order:

Listen to the tales and romanticize,

How we follow the path of the hero.

Boast about the day when the rivers overrun.

How we rise to the height of our halo.

Listen to the tales as we all rationalize

Our way into the arms of the Savior,

Feigning all the trials and the tribulations;

None of us have actually been there.

Not like you.

Ignorant fibbers in the congregation

Gather around spewing sympathy,

Spare me.

None of them can even hold a candle up to you.

Blinded by choices, hypocrites won't [seek / see].

But, enough about the collective Judas.

Who could deny you were the one who

[would have made it, / illuminated]

You'll have a piece of the divine.

Another layer of rhythmic harmony, in the minor, but higher on the scale and lighter, is added at the the end of this small verse and the song takes a heavenly turn, almost a turn from resentment to hope:

And this little light of mine, the gift you passed on to me;

I'll let it shine to guide you safely on your way,

Your way home ...

In the next section, he speaks about the lights going down- the loss of a suffering servant, those who are marked by their love and patience and fidelity to Christ in the midst of great trial- that this loss will leave those with little or no faith at the mercy of the inevitable judgment of God. The music echoes this by the entrance of a new and demanding rhythm from an electric guitar, but as yet still soft and in the distance. At the line, “You’re going home”, the song again takes a turn and we begin to hear a hint of the only melody, a real cry of anguish from the heart of the son left behind:

Oh, what are they going to do when the lights go down

Without you to guide them all to Zion?

What are they going to do when the rivers overrun

Other than tremble incessantly?

High as a wave, but I'll rise on up off the ground.

You [are / were] the light and the way, they'll only read about.

I only pray, [Heaven / God] knows when to lift you out.

Ten thousand days in the fire is long enough, you're going home.

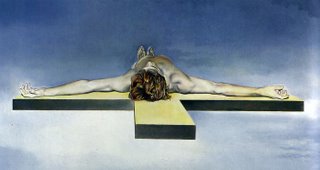

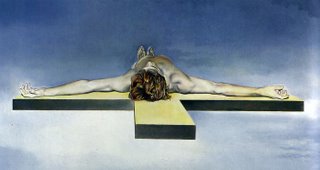

Here the son lets loose the blood-gorged prayer of one who has seen a martyr but as yet does not trust God to take care of her; but understands subliminally both her and his position as penitent and supplicant before the Face of God. I resonate with the cry in the lines, “It’s my time now! Give me my wings!” Although cloaked in demanding language, I find the arching intensity of the music, and the guitar above beginning the melody, the exact representation in music of the intensity of both a martyr’s desire and thirst for God, and the lesser soul’s awe at the work and mystery of the Lord in the life of a suffering soul ascending:

You're the only one who can hold your head up high,

Shake your fists at the gates saying:

"I have come home now!

Fetch me the Spirit, the Son, and the Father.

Tell them their pillar of faith has ascended.

It's time now!

My time now!

Give me my, give me my wings!"

Give me my wings!

You are the light and way, that they will only read about.

Should we all not live, at the deepest levels, in this intensity, and thirst for the Living God? Can we desire something less and be truly human? We can only do this by making the capacity inside ourselves for God, who will then fill us with His torrent. Then we live as martyrs, white and red. A red martyr is one who we are most familiar in story- the ones who gave their lives for Christ by shedding blood. A white martyr is one who, like this singer represents his mother, as accepting suffering, accepting loss, accepting God’s will as over and above their own with love, but to the point of death: internal, unseen, but death nonetheless:

Set as I am in my ways and my arrogance,

Burden of proof tossed upon the believers.

You were the witness, my eyes, my evidence,

Judith Marie, unconditional one.

Daylight dims leaving cold fluorescence.

Difficult to see you in this light.

Please forgive this bold suggestion:

Should you see your Maker's face tonight,

Look Him in the eye, look Him in the eye, and tell Him:

I never lived a lie, never took a life, but surely saved one.

Hallelujah, it's time for you to bring me home.

A white martyr, like the priest-saint who gave his life-blood to hear confessions many hours a day for many years; the nun who desired to die a thousand martyrdoms-and did so all within the pastoral walls of her convent in the daily giving over of her will to Love; the woman who prayed her husband and her children into sanctity at great loneliness and cost to her own dignity- the list goes on and on. We read these stories with some tremulousness and awe, but at a certain distance, as if a wall of glass separates us from these silent sacrifices of love, these heroic sacrifices. Only when we begin to desire to have the capacity for the love of God does He begin, gently, and perfectly contoured to our weaknesses, show us the immensity of any martyrdom; that death is death- of the self or the body. But no martyrdom is true that is not born of –simply, love- and love at an intensity that 10,000 Days portrays. It is that pounding thirst of the doe at the stream, the hunger of Christ for souls- the baptized eros that colors and warms charity. For to give your body to the flames, without this Love, is worth nothing. It would be the stupidest thing I can think of to do. May God preserve us from that.

Rather, it is the angst of seeking the Beloved in the cloud, the handing over of one’s will to Him in the silence and darkness, with no word spoken, no prenuptial agreement, no deposit-guarantee. It is to love, to give oneself because of deep, passionate love for God. The secret is that we could not have this but that He loved us first. He watches ardently at the gate for the approaching soul. He looks for us to have courage, and to cultivate strong desire, which are the necessary preparation for real love to take root: and then martyrdom for love of Christ and the souls He loves- the greatest thing we can, each of us, do.

In these light and dark swirled days of ours, we will most of us, be called to some penultimate moments of white martyrdom: for the sake of truth, or purity, or protection of the innocent. It will only be fruitful in love, love for God and the other. Fruitful in the sense that we do not necessarily know, in this life, what our sacrifices of love and will have done, like a providential wind blowing seeds. I do know that it becomes difficult to look at ten thousand days, or fifteen thousand, in this restless world, searching for the Lord through the dark glass. St. Paul says that we wish to exchange our earthly tent (body) for the heavenly one; but that those who are holy wish to stay or go, as the Lord wishes. This is love. But it doesn’t make the thirst less, but the thirst in itself has its own consolations; and I believe the Lord delights in consolation of His children. I understand now St. Therese’s desire: I want to spend my heaven doing good on earth. To be able to love, deeply and freely, to be allowed some small part in the salvation of others (Christ’s gift).

Yet how can I, like Tool’s writer, make this bold suggestion? In my small, white martyrdoms, I see how weak I am, how narcissistic: but I can hope, and all, all of this is my romance with the Lord. Religare, the root word of religion, means to ‘be tied to’. To be tied to something is to be constricted, and everything on this earth would constrict for ill if we tied ourselves to it- but many of us do. The glory and power of God bursts out clearly, like a pole of light piercing and destroying darkness, when we know that to be tied to God (or tied for the sake of God) is to be tied like as to a life-cord, pulling us up out of the frothing sea; to be tied to God is to be pulled to freedom and love. The Catholic Faith (religion) is the cord, martyrdom the weight of Love.