As St. Thomas Aquinas taught, no man consciously does anything purely evil. In any action, however evil it might be, there is some motivation for good- either the good of the self, or others. The perceived good may not be good in reality, but the point is that it is perceived by the doer as a good on some level.

One can see this easily with small children. Two-year-old Robin believes that the rabbits need some fresh air, and decides to do something about it without checking with the gatekeepers of reality (his parents). He is perceiving two goods: one, his own decision-making ability, and second the good of the rabbits (as he understands it). The rabbits are let loose in the yard, they crawl under the fence, and finally they are lost. Little Robin has created a wake of destruction while believing he is doing good.

It is much more difficult to see this same disorder in adults- mainly because they cover it up with onion skins of rationalization, slowly blocking out the truth to others and to themselves. Let me try to elucidate it with a fictitious example: Andrew is a very intelligent adult in his thirties. As he has grown in his faith, he begins to feel that he has much to give those around him, in terms of counseling and faith-based solutions to people's everyday problems. He sees two goods here, just like little Robin: the good that helping others will do for his own spiritual journey, and the good that he will do for others in helping them with their problems. There is one issue, though, that Andrew does not grapple with: just because he can help, should he? What does God wish him to do? What has God called him to?

Andrew, you see, has learnt a way of looking at his faith such that he is the center of it- but he doesn't know this, awash in the very self-oriented culture of both the modern culture and many churches of the day. Andrew believes in God, but believes in Him as Andrew perceives Him. Andrew does not know that he does not have a faith based on God's presentation of reality but rather a faith built on self-perception, the wishes of oneself.

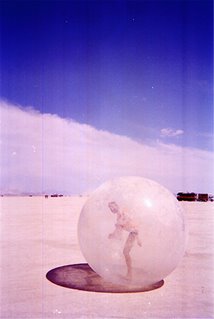

Andrew begins his mission, his savior-like work. Because he is self-oriented, he lives somewhat in an enclosed world, a bit like an observer sitting in the dark under the canopy of 'stars' in a star-gazing room (the ones where the constellations are actually little lights placed in a ceiling). It is a safe and predictable environment, and this safety in a synthetic creation is where Andrew actually derives his incredibly alluring optimism and self-esteem. As he tries to help others with their problems, he is actually helping them to create their own synthetic realities, wherein they can claim to know that God understands them and that they feel certain about the decisions they have made. Andrew, the savior, begins to make disciples of Hell.

The most common problem of evil is not that there are these frightening people who decide they are going to cause havoc. Evil is a much more subtle problem of those who have made their own world, their own understanding of existence. They are people who are, fundamentally, lying to themselves. Thus they can actually believe they are telling others the truth, when in fact, they are creating versions of themselves. A sociopath is the extreme version of this, but a culture bent upon sowing the seeds of radical individualism and self-determination (even in questions of existence and the right thereto: think "abortion") will produce the same evil fruits, albeit on a spectrum of mild insanity to extreme sociopathology.

One only needs to read the history of the City Council of Santa Cruz to understand this kind of middling insanity. They're just now trying to declare Santa Cruz a 'Pro-Choice City', establishing a diabolical city-state religion of sorts, all the while believing they are establishing freedom.

Evil is the absence of good. In terms of a self-oriented person, reality becomes subsumed into their own encased bubble of 'reality'. Three important examples from literature come straight to mind: one is the scene in C.S. Lewis' The Last Battle. All had come through the door of judgement at the end of the world, and the little group of dwarves who had been 'sacrificed to Tash' were sitting huddled together in the midst of a bright meadow (heaven). They could not see anything beyond the darkness of the world of their own making, the cynical 'reality' of the dark stable. Aslan, to please one of the queens, attempts to break into their reality but is rebuffed at every turn. As He tries to help, He turns and says, "I will show you both what I can and cannot do." Even Our Lord cannot break in to a person's selfish construction of reality: Reality Himself is rebuffed, for the deluded person has made himself god and will not trade for the True God.

Another example is the unforgettable character in Flannery O'Conner's A Good Man is Hard to Find, an older woman who is waylaid by robbers along with her family. As they relate to the criminals, it becomes apparent that the older woman has been a tyrant and a destructive influence all her life, all the while believing that she was acting for everyone's good. As reality thrusts itself upon her in the form of a gun, she begins to dismantle her own reality for the truth. The great line in the story is from the mouth of the man who shoots her: "She would have been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life." In this, O'Conner brutally illustrates the terrifying nature of evil and the near-impossibility of a self-deluded person opening himself to reality.

In The Brothers Karamazov, the famous character of the Elder Zossima exhorts the people, "Beware of the lie to yourself". In this great passage, he begs those who come for his advice to search for truth, and above all, to avoid the lie to oneself, for this is the unbreakable prison.

Pride, or fear of hurt is the source of this kind of evil, and it is by learning to view ourselves as humble creatures and not the creators of our own existence, or the creators of whatever information or tradition we inherit, that we begin to live in true reality: thus we live in the good. Humble people, those who stand on the ground, or humus, are those who see themselves in the true light- they seek to see themselves as God sees them, and measure themselves against the standards of Christ and the teachings of the Church. They do not dance around a self-made golden calf, but rather follow God's laws which reflect reality and teach us how to live in it with peace and true love.

Inasmuch as we are humbly searching for the truth, for the True Savior, in reality, we are good. We may not be completely healed, or sane, but the will to strip ourselves of anything or anyone which would keep us from God, or from seeing ourselves how God sees us, is what means we are heading towards being good.